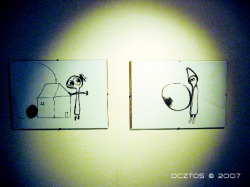

"emberlenyek" - "human creatures"

Exhibition - "Sziv35 Gallery", Budapest - 04. 2007

opened by: Zsuzsa Naszodi, painter

No.: 01

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

No.: 02

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

No.: 03

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

No.: 04

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

No.: 05

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

No.: 06

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

No.: 07

different size

paper - ink - pencil - charcoal

"Magyar Narancs" 03. 05. 2007

Original text by Kriszta Dékei art historian

"Érintések gubanca"

Ocztos István kiállítása

Meg lehet-e maradni gyereknek? Meddig ôrizhetô meg az a különös, ösztönös álomvilág, a gondolkodás szabadsága, amikor a fantázia által kreált valóság igaziságához nem fér kétség? Meddig lehet úgy meghúzni egy vonalat, hogy a társadalom erre kiképzett egyénei (az óvónénik, a tanárok, no meg a lét küzdelmeivel elfoglalt szülôk) ne hívják fel a kisgyermek figyelmét arra, hogy nem létezik háromlábú kutya, ablak nélküli ház, hogy anyukának a valóságban nincsen zsiráfnyaka? Kitörli-e teljesen a sikeres szocializáció a gyermeklét ártatlanságát? Meg lehet-e felnôttként ôrizni a tisztánlátás egyszerûségét? Életben lehet-e tartani azt a tudást, hogy a kisgyerekkor nem egy paradicsomi, idilli állapot, hanem olyan félálom-világ, amelyet megfoghatatlan félelmek és irányíthatatlan érzelmek vezérelnek?

A mûvészet történetében többször is elôfordult, hogy ötletetet merítettek a naív festészetbôl (vámos Rousseau) vagy a graffitikbôl, továbbá elmebetegek és gyerekek rajzaiból – gondoljunk csak a második világháború befejezése után megjelenô art brut-re, s egyik legjelesebb képviselôjére, Dubuffet-re. Amíg azonban náluk ez csak egyszerû mûvészeti eszköz, addig Ocztos Emberlényei belsô forrásból táplálkoznak. Nem alkalmaz, imitál, nem ihletet keres a gyerekrajzok tiszta és redukált világában. Egyszerûen “csak” megôrizte és megvédte magában a gyerekkor ôsi szabadságát és azt az örömöt, amit egy önkéntelenül felvitt, kanyargó vonalrajz okoz. Mûveinek értékét is éppen az a kettôsség okozza, amely a tudatos felnôtt-nézôpont és az öntudatlan gyermeki látásmód között feszül, s amelybôl ezek az autonóm, egyszerre szorongató és rokonszenves gyermek-felnôtt rajzok táplálkoznak.

Ocztos vonalaiból különös, emberszerû és egyszerû lények alakulnak ki. Kicsiny lábak, pácikához hasonlító kezek, hol csodálkozó, hol riadt tekintetek. A fekete tusrajz csak a testváz kontúrját fogja össze, nincsenek színek és távlatok, csak az idôtlen létezés. Volt, lehetett azonban valamiféle, organikus születés: egyes alakok mintha még saját burkukat ôrizgetnék, másuk már kibábozódtak; szárnyacskájuk hátukra simul. Vannak köztük “antennásak” is, akik egyetlen vonallal kapcsolódnak a külvilághoz, a kép terén kívül esô valósághoz. A hol kedves, hol ijesztô alakok néha csak egy házacska mellett álldogálnak, néha azonban különös kapcsolatba kerülnek egy lebegô gömbbel, megérintik, tapogatják a kozmosz kicsinyített mását. Elbágyadt, várakozó, dühös vagy kiábrándult pillangók, akik most éppen felmutatják nekünk meseszerûen valós történeteiket.

A tenyérnyi, elegáns ceruzarajzok világa sokkal “hétköznapibb”– egymáshoz kötôdô emberpárok, magányos alakok állnak össze az egyetlen, megszakítatatlan vonalból felvitt ceruzahálóból. Társas magányuk furcsa tánc, papírba dermedt lépéseiket mintha egy ismertelen erô vezetné. Marionettbábok egy olyan, vonzásokkal és taszításokkal terhelt környezetben, ahol egy érintés éppúgy összekapcsolhat, mint ahogy szét is választhat. A kis kezekbôl kitüremkedô aurafelhôk, megnagyobbodott tenyérnyomok áthatolnak a másik testén, a párok egyszerre ejtik rabul és taszítják el egymást. Nincs tér és nincs idô, csak ez a véget nem érô, örökös küzdelem, az érzelmek, akaratok, vágyak egymásba gubancolódó hálója.

A kiállításon megfigyelhetô, hogy bár átültethetô a rajzoknál alkalmazott légies és fesztelen mozdulatsor egy másik technikába, de a kígyózó vonalrajz könnyedsége összeroppan a szénrajz sötét, vastag nyalábjai alatt. A szénrajzokon is felbukkanó, összekötözött emberpár motívuma elveszti minden szépségét; a kapcsolatokat behálózó nyers erôvonalak, a feketére satírozott hátterek, fenyegetôen tornyosuló gömbök egy szorongató világot állítanak elénk. E hiányos és torz emberlények legalább annyira a rémálmok világában laknak, mint a valóságban. Hogy pontosan hol, azt mindenki maga dönti el. Ocztos rajzain ugyanis egyfajta ôsi tudattalan tör felszínre, amelyre mintegy rárétegzôdnek a felnôttlét nehezen verbalizálható érzelmi tapasztalatai. Játékosan komor és tömör szimbólumokat, élet-sûrítményeket láthatunk, amelyeket nem érdemes dekódolni, nem elegendô csak nézni, hanem valamilyen módon érezni kell. Vissza kell lépnünk önmagunkba, személyiségünk ritkán látogatott tartományába ahhoz, hogy megérinthessenek minket e mûvek. S hogy megijedünk, szomorkodunk, kacarászunk, vagy éppen idétlenül vihogunk – ez már csak rajtunk, s a bennünk megôrzött gyermeki ösztönökön múlik.

Dékei Kriszta

SZÍV35 Galéria, Bp. VI. Szív u. 35. Nyitva május 12-ig, hétfô-péntek 14.00–18.00 szombat-vasárnap 14.00–21.00.

2007.

"A Tangle of Touch"

an exhibit by István Ocztos

Is it possible to preserve the child inside of you? How long can the fantastic, instinctive dream-world be upheld? Is it possible to retain freedom of thought, that unquestionable reality created by your own imagination? How far can you go before society’s “qualified” individuals (kindergarten teachers, school teachers, and parents preoccupied with the struggles of existence) inform kids that three-legged dogs, houses without windows, and mommies with giraffe necks don’t exist? Does successful socialization completely erase the innocence of a child’s world? Is it possible to see clearly and simply as an adult? Can the knowledge be sustained that childhood is not a blessed, idyllic state but rather a partial dream-world which is ruled by inexplicable fears and uncontrollable emotions?

Throughout history, artists were often inspired by primitive painting (e.g. “Vámos” Rousseau), graffiti, and drawings made by children and the mentally insane. One example is the Art Brut movement appearing after the end of World War II and the work of its most eminent representative, Dubuffet. While these painters merely employed techniques in an outward manner, Ocztos’s Human Creatures are nourished from an inner source. Ocztos does not apply, imitate, or search for inspiration in the clear and reduced world of children’s drawings. He “simply” managed to preserve and protect the freedom of childhood along with the joy that a spontaneously composed, curving line-drawing brings. The value of his work stems exactly from this dichotomy, sustained between the conscious adult perspective and a child’s instinctive way of seeing. This is what nurtures the autonomous child/adult drawings, simultaneously full of intensity and congeniality.

The lines of Ocztos’s drawings form odd, human-like figures: smallish feet, stick arms, their expressions sometimes surprised, other times startled. The black tint-drawing merely holds together the contour of the body structure; there are no colors or vistas, only timeless existence. There might have been, however, some sort of organic naissance: certain figures seem to still retain their original shells, while others have shed them, wings pressed to their backs. Some of the figures have “antennae,” linked to the outside world – the world outside the picture – through a single line. At times, the pleasant or intimidating figures stand near a little house; at other times they come into strange contact with a floating orb, touching it, caressing a small-scale version of the cosmos. They are languid, waiting, angry, or disillusioned butterflies, who present their dreamy but real stories to us at this moment in time.

The world of the palm-sized, elegant pencil drawings is much more “ordinary:” linked couples and lonely figures are created in a pencil network of a single, unbroken line. Their collective loneliness is a strange dance; their steps frozen on paper seem to be directed by an unknown power. They are marionettes in an environment weighed down by attraction and resistance, where a touch is capable of connecting and dividing at the same time. The little hands emit little aura clouds; the enlarged handprints penetrate the other’s body; the pairs capture and push each other away simultaneously. There is no time or space, just an endless struggle: the tangled net of individual will, feeling, and desire.

While looking at the exhibited works, one may observe that it is possible to transfer the airy and uninhibited series of movements to another technique, but the lightness of the serpentine line-drawings is crushed by the thick, dark streaks of the charcoal drawings. The motif of the linked human figures appear in the charcoal drawings too, but loses all of its beauty. The raw lines of force entangling the connections, the blackly shaded backgrounds, the threateningly towering spheres present us with a stifling world. These incomplete and distorted creatures dwell as much in a world of nightmares as they do in reality. It is up to the viewer to decide exactly where they are situated. A primordial unconscious state gushes to the surface in Ocztos’s drawings and the emotional experiences of adulthood, so difficult to verbalize, seem to form layers upon this state. We see playful, yet grave, dense symbols and condensed lives here. There seems to be no point in decoding them, but just looking at them isn’t enough. They need to be felt in some way. We must step back into our own selves, into a rarely visited territory of our personality in order for these works to touch us. The child’s instinct preserved inside of us will bring out a chuckle or silly laugh, our fright or sadness.

Kriszta Dékei

SZÍV35 Gallery, Budapest, 6th District, Szív u. 35. On display until May 12th. Open Mon.- Fri. 2pm-6pm. and Sat.- Sun. 2pm-9pm. 2007.

Translated by: Ildiko Noemi Nagy